Implementing Base64 from scratch in Rust

In this article we’re taking a closer look at the Base64 algorithm and implement an encoder and decoder from scratch using the Rust programming language. Base64 is quite an easy to grasp algorithm and certainly fun to implement yourself! Let’s dive right in!

What is Base64?

Base64 is an encoding algorithm that was primarily designed to encode binary data for use in text-based algorithms by using 64 different ASCII characters to represent the bits. For example email attachments or embedding image data directly into a img tag.

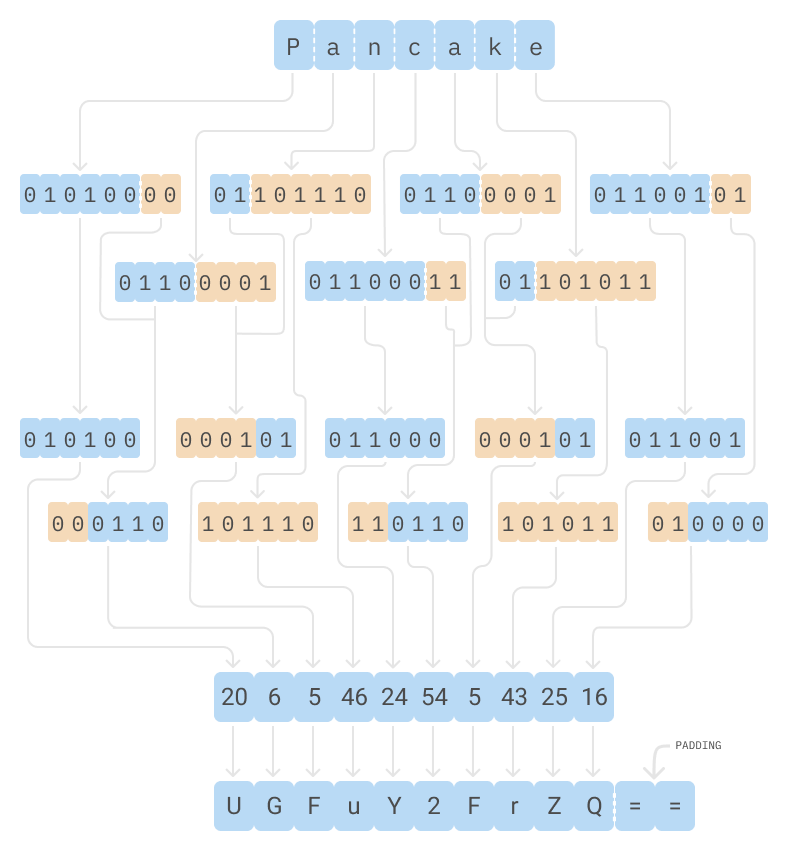

Base64 works by breaking up the original binary in chunks of 3 bytes (24 bits) and splitting these 24 bits into 4 groups of 6 bits. These 6 bits translate to a number anywhere from 0 (0b000000) through 63 (0b111111) that are mapped to 64 ASCII characters.

Base64 encoder schematic

The original Base64 alphabet uses A-Z uppercase, a-z lowercase, the digits 0 through 9 and special characters + and /. The = is used for padding at the end of the output string, so that we always end on a multiple of four bytes. This is Base64 in a nutshell, for a thorough deep dive into Base64, give this excellent article a read!

The puzzle pieces

Let’s walk through the steps that are required to make encoding into and decoding from Base64 work:

Encoding data to Base64 is fairly simple:

- Take the original binary input

- Chop this stream up in slices of 3 bytes (24 bits)

- Chunk each of these 24 bits again in 6-bit parts

- Convert these 6 bits into an index (0-63)

- Assign an unique character that can be found at that index in the Base64 table

- Append padding characters (

=) until we until the total encoded string reaches a multiple of four bytes. - et voila!

Decoding is basically working backwards:

- Strip off the padding (

=) - Iterate over the remaining bytes in chunks of four bytes

- Look up each ASCII character in the table to get the original numeric index

- From these indexes, take the upper 6 bits and stitch them back together

- You end up with a multiple of 8 bits which is your original data

Let’s get to work!

Ok, enough theory already! Let’s get to work! Let’s setup a new Rust project (binary) and implement our first few modules:

1cargo new base64 --bin

Implementing an encoding alphabet

As mentioned previously the default Base64 implementation uses an alphabet containing A-Z, a-z, 0-9, + and /. However I want our alphabet to be configurable, enabling us to provide an Emoji-based alphabet instead for example 👻

To make it configurable, let’s figure out a common API that we can implement our configurable alphabets against. We’re describing this API in what Rust calls a trait (comparable to an Interface in Java, Go or C#).

Defining our Alphabet trait

There are basically three operations that our alphabet should be able to perform; Going from an index to a character, going from a character back to the original 6-bit index and getting the character used for padding.

Let’s create a new src/alphabet.rs file inside our project and get going:

1pub trait Alphabet {

2 fn get_char_for_index(&self, index: u8) -> Option<char>;

3 fn get_index_for_char(&self, character: char) -> Option<u8>;

4 fn get_padding_char(&self) -> char;

5}

Defining the classic Base64 alphabet implementation

Now that we wrote the contract of what an alphabet should be able to perform, let’s create the classic Base64 alphabet first.

Like we talked about in the beginning of this post, the classic alphabet uses a-z, A-Z, 0-9 plus +, / and = for padding.

We’re creating an empty struct and call it Classic, this will act as the type to call the methods on. Let’s also supply an implementation for the Alphabet trait and place all this into the same src/alphabet.rs file for now.

1// ... snip trait declaration

2

3pub struct Classic;

4

5const UPPERCASEOFFSET: i8 = 65;

6const LOWERCASEOFFSET: i8 = 71;

7const DIGITOFFSET: i8 = -4;

8

9impl Alphabet for Classic {

10 fn get_char_for_index(&self, index: u8) -> Option<char> {

11 let index = index as i8;

12

13 let ascii_index = match index {

14 0..=25 => index + UPPERCASEOFFSET, // A-Z

15 26..=51 => index + LOWERCASEOFFSET, // a-z

16 52..=61 => index + DIGITOFFSET, // 0-9

17 62 => 43, // +

18 63 => 47, // /

19

20 _ => return None,

21 } as u8;

22

23 Some(ascii_index as char)

24 }

25

26 fn get_index_for_char(&self, character: char) -> Option<u8> {

27 let character = character as i8;

28 let base64_index = match character {

29 65..=90 => character - UPPERCASEOFFSET, // A-Z

30 97..=122 => character - LOWERCASEOFFSET, // a-z

31 48..=57 => character - DIGITOFFSET, // 0-9

32 43 => 62, // +

33 47 => 63, // /

34

35 _ => return None,

36 } as u8;

37

38 Some(base64_index)

39 }

40

41 fn get_padding_char(&self) -> char {

42 '='

43 }

44}

First things first, we define an empty struct called Classic, such a type in Rust-land is called a zero-sized-type. Due to the lack of fields, it will only exist in Rusts type system, once the compiler chewed its way through our code, there will be no trace of this struct anymore! It is however a very neat way of passing trait implementations around and that is why we are using it.

Following the struct declaration are a few constants followed by the implementation of the Alphabet trait on our Classic struct. The implementation itself makes use of the fact that characters in the ASCII alphabet are defined mostly in sequence. For example: A through Z uppercased have indexes 65 through 90, the same is true for both a through z lowercased and the digits 0 through 9.

We make use of this by pre-calculating an offset between our Base64 index (0-63) and the index in the ASCII alphabet (65-90, 97-122, etc). Then using the match operator match on a specific range, apply the correct offset and return the result as a byte.

Mission accomplished 💪

Building the Encoder! 🙌

Now that we have defined how our alphabet should work, let’s get on to building the encoder part of our project. We’ll create a new module inside src/encoder.rs and bring the Alphabet trait and Classic implementation into scope:

1use crate::alphabet::{Alphabet, Classic};

The next step is setting up a few smaller functions that will take on the heavy lifting of the encoding part.

Splitting it up!

Let’s start with our split function:

1fn split(chunk: &[u8]) -> Vec<u8> {

2 match chunk.len() {

3 1 => vec![

4 &chunk[0] >> 2,

5 (&chunk[0] & 0b00000011) << 4

6 ],

7

8 2 => vec![

9 &chunk[0] >> 2,

10 (&chunk[0] & 0b00000011) << 4 | &chunk[1] >> 4,

11 (&chunk[1] & 0b00001111) << 2,

12 ],

13

14 3 => vec![

15 &chunk[0] >> 2,

16 (&chunk[0] & 0b00000011) << 4 | &chunk[1] >> 4,

17 (&chunk[1] & 0b00001111) << 2 | &chunk[2] >> 6,

18 &chunk[2] & 0b00111111

19 ],

20

21 _ => unreachable!()

22 }

23}

As you can see in the function signature, the split function takes a slice of bytes (&[u8]) and returns a Vec<u8>. It converts the input of up-to 3 bytes into an output of up-to 4 bytes. Essentially converting the 8-bit unsigned integers into 6-bit.

To achieve this, we use bitwise operations to shuffle the bits around. In case of a 1-byte input, we return two bytes where the first 6 bits of the input byte are returned as the first output byte, the last two bits of the input byte are returned as the second byte. In case of a 3 byte input, we follow the same kind of steps to piece different parts of the bytes together to form 4 output bytes each holding 6 bits of information.

Encoding using our Alphabet

Now that we have a mechanism to convert from 8-bit numbers to 6-bit numbers, let’s slice the input data into 3-byte chunks and run them through our split function. Once they’re split, we can convert each chunk by looking up the 6-bit number in our alphabet:

1pub fn encode_using_alphabet<T: Alphabet>(alphabet: &T, data: &[u8]) -> String {

2 let encoded = data

3 .chunks(3)

4 .map(split)

5 .flat_map(|chunk| encode_chunk(alphabet, chunk));

6

7 String::from_iter(encoded)

8}

The encode_with_alphabet function shown above takes the alphabet to encode against en the original input string to encode. The first step is to slide the input in 3-byte chunks and feeding it into our split function that will return a Vec<u8> of maximum 4-bytes.

Passing each 6-bit number to encode_chunk using flat_map will ensure we’re flattening the Vec<char> while we’re at it and lastly we consume the iterator by passing it to String::from_iter!

Note: For that last trick (using String::from_iter to build a string from an iterator) to work, we’ll need to bring FromIterator trait into scope, see:

1use std::iter::FromIterator;

encode_chunk internals

As promised, let’s zoom in a bit on the encode_chunk function we’re using above. The function signature tells us that this function will take anything that implements the Alphabet trait (which our Classic alphabet does) and a chunk of our bytes (more specifically the Vec<u8> that came rolling out of the split function earlier.

1fn encode_chunk<T: Alphabet>(alphabet: &T, chunk: Vec<u8>) -> Vec<char> {

2 let mut out = vec![alphabet.get_padding_char(); 4];

3

4 for i in 0..chunk.len() {

5 if let Some(chr) = alphabet.get_char_for_index(chunk[i]) {

6 out[i] = chr;

7 }

8 }

9

10 out

11}

This function starts off by setting up a Vec<char> that acts as our output buffer, to make our lives easier we’re pre filling the buffer with 4 padding characters. Note that we tagged the buffer as mutable so we can overwrite the padding characters with actual data as we’re going along.

Inside our loop we take the 6-bit number, look up the character in our alphabet by index and replace the padding symbol with the actual data, if available. At the end of the loop we just return the output buffer.

That’s it! That’s all there is to do to get your data Base64 encoded! I wont bore you with the tests but for those interested, check em out on the repo

Decoding

Now that we can turn any arbitrary binary blob into a easy-to-transmit Base64 string, we obviously want to retrieve our original data from the encoded blob, otherwise we just built a data corrupter ;)

Let’s implement our decoder in a separate module in src/decoder.rs. Much like with our encoder we’re going to need our Alphabet trait together with our Classic implementation. Let’s bring these into scope, like so:

1use crate::alphabet::{Alphabet, Classic};

Let’s dive right in and define a decode_using_alpabet function that, much like our encode_using_alphabet function takes the alphabet to do the decoding against and the encoded string to perform the decoding on.

1pub fn decode_using_alphabet<T: Alphabet>(alphabet: T, data: &String) -> Result<Vec<u8>, io::Error> {

2 // if data is not multiple of four bytes, data is invalid

3 if data.chars().count() % 4 != 0 {

4 return Err(io::Error::from(io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput))

5 }

6

7 let result = data

8 .chars()

9 .collect::<Vec<char>>()

10 .chunks(4)

11 .map(|chunk| original(&alphabet, chunk) )

12 .flat_map(stitch)

13 .collect();

14

15 Ok(result)

16}

The first thing we do is run a quick check if the data is indeed a multiple of four bytes, which is one of the characteristics of base64 encoded data. If it does not match these requirements, we’ll return an error. When the data is valid, we split the string into its chars and slice it in chunks of 4 char’s. Each slice is fed through the original function that will fetch the original char from the alphabet which is flat_map‘ed through the stitch function.

Getting the original

1fn original<T: Alphabet>(alphabet: &T, chunk: &[char]) -> Vec<u8> {

2 chunk

3 .iter()

4 .filter(|character| *character != &alphabet.get_padding_char())

5 .map(|character| {

6 alphabet

7 .get_index_for_char(*character)

8 .expect("unable to find character in alphabet")

9 })

10 .collect()

11}

The original function takes an Alphabet trait object again and a slice of chars (maximum of 4-bytes). It filters the padding characters and uses the looks up the left-over characters in our alphabet. Returning a Vec of bytes as the original data.

Stitch it back together

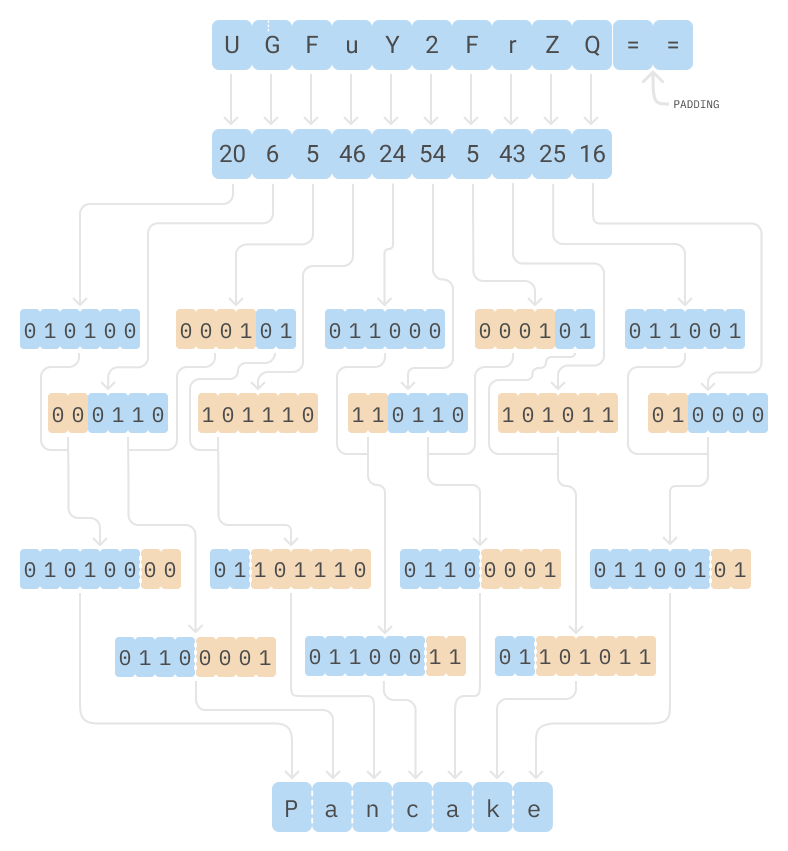

Pretty much as a reverse of split we’re taking the various bits from two or more bytes and put it back together much like a carefully constructed Lego Millennium Falcon. It takes a Vec of bytes and returns another Vec of bytes, containing a maximum of three 8-bit numbers.

1fn stitch(bytes: Vec<u8>) -> Vec<u8> {

2 let out = match bytes.len() {

3 2 => vec![

4 (bytes[0] & 0b00111111) << 2 | bytes[1] >> 4,

5 (bytes[1] & 0b00001111) << 4,

6 ],

7

8 3 => vec![

9 (bytes[0] & 0b00111111) << 2 | bytes[1] >> 4,

10 (bytes[1] & 0b00001111) << 4 | bytes[2] >> 2,

11 (bytes[2] & 0b00000011) << 6,

12 ],

13

14 4 => vec![

15 (bytes[0] & 0b00111111) << 2 | bytes[1] >> 4,

16 (bytes[1] & 0b00001111) << 4 | bytes[2] >> 2,

17 (bytes[2] & 0b00000011) << 6 | bytes[3] & 0b00111111,

18 ],

19

20 _ => unreachable!()

21 };

22

23 out.into_iter().filter(|&x| x > 0).collect()

24}

And this is how that looks in a schematic: Base64 decoder schematic

Nice! The encoder and decoder are done! For completeness we obviously also included tests for our decoder ✨✨

Piecing it together

Notice that we wrote all these pieces but our fn main() still has the placeholder println!("Hello, world!"); in it? This is obviously unacceptable, so let’s get back to it and crank out a simple CLI that will take a command line argument and read from STDIN 💪

First things first; let’s convert our fn main() function so that it will return a Result type. We do this to make our lives easier in terms of error handling, you’ll see why in a bit!

1fn main() -> Result<(), CLIError> {

2

3}

Notice that we’re returning an empty tuple (or unit in Rust) for the success type and a CLIError as the error type, however we have not yet defined our CLIError. Let’s do that right now before the compiler yells at us:

1use std::fmt;

2

3enum CLIError {

4 TooFewArguments,

5 InvalidSubcommand(String),

6 StdInUnreadable,

7 DecodingError,

8}

9

10impl std::fmt::Debug for CLIError {

11 fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

12 match &self {

13 Self::TooFewArguments =>

14 write!(f, "Not enough arguments provided"),

15

16 Self::InvalidSubcommand(cmd) =>

17 write!(f, "Invalid subcommand provided: \"{}\"", cmd),

18

19 Self::StdInUnreadable =>

20 write!(f, "Unable to read STDIN"),

21

22 Self::DecodingError =>

23 write!(f, "An error occured while decoding the data"),

24 }

25 }

26}

In the code above we define the enum CLIError that describes pretty much everything that can go wrong when calling our binary. For example; for whatever reason reading from the STDIN is not successful or we’re calling our executable without providing a valid subcommand. Notice that in the case of the unknown subcommand we’re also keeping track of what exactly is passed, giving our users a bit more context around the error.

Notice that next to defining our CLIError we also make it implement the Debug trait. This trait pretty much describes how the variants inside the enum can be turned into a printable string when returned as part of the error type.

The next step is writing a few functions that will make reading from STDIN, encoding and decoding a bit easier:

1use std::io::{self, Read};

2

3fn read_stdin() -> Result<String, CLIError> {

4 let mut input = String::new();

5 io::stdin()

6 .read_to_string(&mut input)

7 .map_err(|_| CLIError::StdInUnreadable)?;

8

9 Ok(input.trim().to_string())

10}

11

12fn encode(input: &String) -> String {

13 encoder::encode(input.as_bytes())

14}

15

16fn decode(input: &String) -> Result<String, CLIError> {

17 let decoded = decoder::decode(input).map_err(|_| CLIError::DecodingError)?;

18

19 let decoded_as_string = std::str::from_utf8(&decoded)

20 .map_err(|_| CLIError::DecodingError)?;

21

22 Ok(decoded_as_string.to_owned())

23}

Note the read_from_stdin function also returns a Result<String, CLIError>. It will attempt to read from STDIN and write the contents to a string. If this succeeds it will return the Ok variant with the string value, but if this fails, we will map the error to a CLIError::StdInUnreadable error which will be pretty printed in our console.

The next two functions (encode and decode) are pretty much just wrappers around our library functions encoder and decoder that will take in a reference to a string and return a owned string. To ensure we are able to use our encoder and decoder modules, let’s link them to the main executable:

1mod alphabet;

2mod decoder;

3mod encoder;

Final stretch! Let’s fill in our main() function:

1fn main() -> Result<(), CLIError> {

2 if std::env::args().count() < 2 {

3 return Err(CLIError::TooFewArguments);

4 }

5

6 let subcommand = std::env::args()

7 .nth(1)

8 .ok_or_else(|| CLIError::TooFewArguments)?;

9

10 let input = read_stdin()?;

11

12 let output = match subcommand.as_str() {

13 "encode" => Ok(encode(&input)),

14 "decode" => Ok(decode(&input)?),

15 cmd => Err(CLIError::InvalidSubcommand(cmd.to_string())),

16 }?;

17

18 println!("{}", output);

19

20 Ok(())

21}

As you can see we can make a functional CLI within just a few lines of pure Rust without pulling in external dependencies. By using the Result<T, E> type and the question mark operator (?) we’re essentially short-circuiting the returned Result types only continuing down the happy path, or returning the error as the return value of the containing function in case of an error.

That is it! That is all we need to make a fully functioning Base64 implementation from scratch in Rust and wrap it in a CLI tool. Usage:

1# encoding

2echo 'fluffy pancakes' | cargo run -- encode

3> Zmx1ZmZ5IHBhbmNha2Vz

4

5# and the reverse

6echo 'Zmx1ZmZ5IHBhbmNha2Vz' | cargo run -- decode

7> fluffy pancakes

Thank you for reading! The finished project can be found on GitHub :)